-Rajesh

Tyagi/ 24.2.2015

History had been cruel and unjust in imposing the task of world socialist revolution upon

the shoulders of Russian proletariat, that existed not more than a droplet in

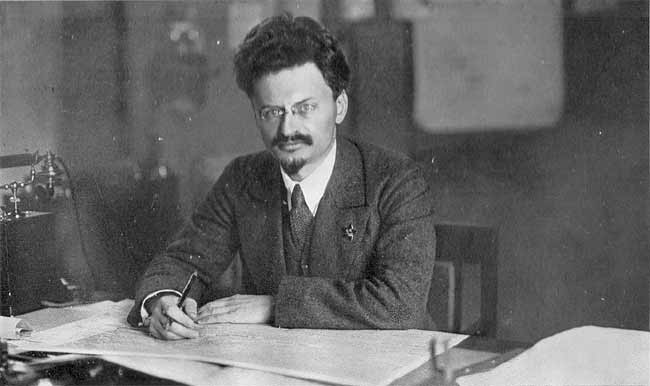

the vast ocean of peasant mass in backward Russia, at the advent of last century. But alongside this, the Russian proletariat was the first to be

blessed with two magical weapons- the leadership under Lenin and Trotsky, and

the Party oriented ultimately to their program.

Despite all

zig-zags before and even after February revolution by the Bolshevik leaders,

those epigones of Leninism, ‘Red October’ was created through unique blending

of best of Lenin and Trotsky. Trotsky turned to Lenin’s approach on the

question of Party, abandoning his misbelief in non-party positions, and Lenin

turned to Trotsky’s ‘Permanent Revolution’ abandoning his false theory of ‘two

stage revolution’ and ‘two class dictatorship’. Lenin’s April thesis was the

beautiful embodiment of this blending and shunning of whatever was disproved

and rejected by the February Revolution. Commenting on this secondary aspect of

theory vis a vis reality of life, that brilliant genius, Lenin had remarked, “the

theory is brown my friend, but the tree of life is green”.

Soviet republic had come into existence through the earth shaking October revolution, tremors of which were felt with notable intensity all over the capitalist world. The spectre of communism, that haunted Europe in times of Marx, and at which ruling classes trembled since then, had incarnated itself.

October

revolution was born amidst the World War-I, that had divided the Imperialist

world and presented additional hope for survival of October revolution.

However, the primary prospects of not only survival but of victory and advance

of the revolution onto world scale, had hinged upon the victory of the

proletariat in far advanced Europe, especially Germany, where revolution was

already in the air. Leaders of the revolution were in high hopes.

Yet,

confronted with the ground realities, the route to revolution did not prove to

be so smooth. Events unfolded themselves far differently than what the most

brilliant leaders of the world proletariat- Lenin, Trotsky, Rosa, Leibknecht

had envisioned them in prospect.

Through Organisation

of the ‘Third International’ (Comintern) and the agitation conducted by it, the

‘Red October’ had reinforced and reiterated its pledge to prepare necessary

conditions for transformation of the war into a World Socialist Revolution.

However,

immediately after its victory, the Soviet republic was put to trial in

civil-war inside and military aggressions outside.

The incident

of Brest-Litovsk, posed such a challenge to Soviet Power. Our understanding on

Brest-Litovsk is very important to correctly understand the proletarian

internationalism pursued by the Soviet state and its leaders like Lenin and

Trotsky.

This

understanding is especially important as the Stalinists attempt to distort the

struggle of young soviet state against the oppressive treaty of Brest-Litovsk

forced upon it by Imperialism, falsely portraying the same as a personal strife

between Lenin, supposed to be defending ‘socialism in one country’ and Trotsky

bent upon to sacrifice the soviet state for a world revolution. The same is blatant lie and falsification of

the positions of the leaders of the October revolution, who all agreed upon

waging a ‘revolutionary war’ against capitalist countries, both through

revolutionary upheavals and revolutionary wars of Red Army, as the supreme

strategic task of the soviet state.

Tsarist

regime saw its salvation in the war, after its failure to stabilize Russia

after the uprising of 1905, even by offering concessions like land reforms and

a Duma, and entered the WW-I in 1914, on the side of France and Britain, later

joined by the US. WW-I, found Russia in acute political crisis. As the Russian peasants

and workers rallied around the call to defend the ‘Fatherland’ Russia’, the Tsarist

regime took a respite.

Russia’s entry into war, by forcing the Germans to deploy troops on the eastern front, thwarted the German plan for a swift victory.

However, Russia

had to pay the biggest price for this war. In 1914 alone, 250,000 soldiers died

on front, more were maimed and disabled. Although the Russian army had a number

of successes in 1916, but by the end of 1916 some 1,700,000 Russian soldiers

had died. The war resulted in acute food shortages and unemployment, leading to

widespread unrest.

As 1917

dawned, partisan riots and mutinies precipitated into a political revolution, forcing

Tsar Nicholas to abdicate in February. However, the provisional government

under Prince Lvov and then Kerensky, refused to withdraw from the War.

Resentment against the war spread to trenches and the Russian armies started to

fall apart with soldiers disobeying the officers. During the summer of 1917,

Russian soldiers deserted en-masse. The soldiers returned home to support the Bolsheviks,

who promised to take Russia out of the war.

Since advent

of WW-I in 1914, pivotal to Bolshevik political agitation was the pledge to

bring Russia out of the catastrophe of the War as part of the struggle of world

proletariat against imperialist war. However, this anti-war program was not the

program of pacifism, but was inextricably bound up with the movement of the

world proletariat against the Imperialist war, battle cry of which in all

engaged countries was: “Enemy is within. Turn your guns away from borders and

towards your own capitals. To revolution, comrades”. The revolutionary policy

was based upon ‘revolutionary defeatism’ and ‘proletarian internationalism’

that called upon the proletariat of all countries to work for defeat of their

own governments in the war and transform thereby war into revolution. This was

opposed to ‘social chauvinism’ of false socialists of the Second International

that advocated national defencism under the fiction of ‘defence of motherland’.

After

victory of revolution in October, Bolshevik government led by Lenin and

Trotsky, set out to take measures on national and international scale to

subvert the Imperialist war and transform it into a revolutionary war of the

world proletariat against Imperialism.

As commissar

for foreign affairs Trotsky forthwith published the secret treaties of the

Tsarist government to embarrass the Imperialist powers on both sides of the War

and to encourage the working class to fight against their own governments, which

had shameful secret war pacts with Tsarist government.

Outlining

his strategy, Trotsky issued the following note, On 27 October (9 November)

1917, on Secret Diplomacy and Secret Treaties: “In

undertaking the publication of the secret diplomatic documents relating to the

foreign diplomacy of the Tsarist and the bourgeois coalition governments ... we

fulfil an obligation which our party assumed when it was the party of

opposition.

Secret

diplomacy is a necessary weapon in the hands of the propertied minority, which

is compelled to deceive the majority in order to make the latter serve its

interests. Imperialism, with its worldwide plans of annexation, its rapacious

alliances and machinations, has developed the system of secret diplomacy to the

highest degree.

The struggle

against imperialism, which had bled the peoples of Europe white and destroyed

them, means also a struggle against capitalist diplomacy which has reasons

enough to fear the light of day. The Russian people and, with it, the peoples

of Europe and the whole world, ought to know the precise truth about the plans

forged in secret by the financiers and diplomatic agents ... The abolition of

secret diplomacy is the primary condition of an honourable, popular, really

democratic foreign policy.”

“….Our

programme formulates the burning aspirations of millions of workers, soldiers

and peasants. We desire the speediest peace on principles of honourable

co-existence and co-operation of peoples. We wish the speediest overthrow of

the rule of capital. Exposing to the whole world the work of the ruling classes

as expressed in the secret documents of diplomacy, we turn to the toilers with

the appeal which constitutes the firm foundation of our foreign policy:

Proletarians of all countries unite!” Trotsky added.

Pursuant to

its policy of coming out of the imperialist war, the Soviet government,

immediately after victory of October revolution, offered to withdraw from the

war and proposed separate peace treaty with Germany. The Germans, however, imposed

extremely oppressive conditions for the back-out and threatened a military

assault on failure.

Formal negotiations

between Russia and Germany started on December 9, in Polish town of

Brest-Litovsk, then under occupation of Germany. Leon Trotsky, the political

and military strategist and co-leader with Lenin in October revolution, Foreign

Commissar of Soviet Union at that time, was selected by the Soviet State and

Party to make the negotiations.

Bidding for

complete poaching of Russia, the Kaiser regime in Germany, armed from head to

toe, sought to impose a very harsh peace treaty upon Soviet Union. In response,

Bolshevik leaders were divided in two main factions.

Majority

faction was led by Bukharin, which rejected the peace negotiations outright and

advocated a ‘Revolutionary War’ with Germany. The faction was supported by huge

majority among the soviets and workers and peasant mass. Minority faction, was led by Lenin and

Trotsky, which instead of entering into an instant war with Germany, proposed

to ‘wait’ till upswing of the German revolution.

Though both

Lenin and Trotsky deemed it impossible to fight a ‘revolutionary war’, against

Germany, as advocated by majority faction, in absence of a Revolutionary Army,

yet despite their unity in favour of a ‘wait’ for German revolution and against

the proposal of entering into instant war, the two leaders in minority faction

differed on the tactics, during this ‘wait’. While Lenin was of the opinion

that the Treaty proposed by Germany should be accepted forthwith, only to be

repudiated after socialist revolution in Germany, Trotsky argued in favour of

prolonging the negotiations with Germany as far as possible and till impending

German revolution approaches, and to sign the Treaty only in face of an actual German

assault. Trotsky, anticipated that the revolutionary agitation by the soviet

state, during these negotiations and even the probable aggression by Germany

against Revolutionary Soviet Union, could spark a revolution in Germany and

other countries of Europe.

The common

objective of the policy pursued by the minority faction was to bargain time at

Brest-Litovsk, hoping that very soon the revolutionary movement in the West

would overthrow German Imperialism and coincide with revolution in Russia.

The

differences among all factions of Bolsheviks were however of mere tactical importance,

aimed at dealing with specific situation, presented by history. However, there

was no dispute as to the strategic task before the Soviet State to ignite ‘Revolutionary

Wars’ hand in hand with revolutionary uprisings, against the imperialist

powers. Despite strategic unity among Bolsheviks, the episodic tactical

differences among them were merely the product of utter military weakness of

the new born Soviet State, which was to vanish very soon, with organization of

the Red Army.

Referring to

this strategy of ‘revolutionary wars’, unanimously accepted by Bolsheviks, Lenin,

far ahead of October revolution, wrote in ‘Some Theses’ in Sotsial-Democrat in

1915: "To the

question what the party of the proletariat would do if the revolution put it in

power in the present war, we reply: we should propose peace

to all the belligerents on condition of the liberation of the

colonies, and of all dependent and oppressed peoples not enjoying

full rights. Neither Germany nor England nor France would under their present

governments accept this condition. Then we should have to prepare to wage a

revolutionary war i.e. we should not only carry out in full by the most

decisive measures our minimum programme, but should systematically incite to

insurrection all the peoples now oppressed by the Great Russians, all colonies

and dependent countries of Asia (India, China, Persia, etc) and also - and

first of all - incite the proletariat of Europe to insurrection against its

governments and in defiance of its social chauvinists."

To be sure,

even before 1917, Bolshevism stood for ‘Revolutionary Wars’, the wars against

imperialism, combining the armed struggle of the Red Army with the insurrection

of the workers of Europe and the toilers of the oppressed nations.

Reiterating

the Bolshevik pledge for withdrawal from the ongoing Imperialist war, and to

transform the same into ‘revolutionary war’, Lenin wrote in late September,

1917: "If the least probable should occur, i.e. if no belligerent state

accepts even an armistice, then the war on our side would become a really

necessary, really just and defensive war. The mere fact that the proletariat

and the poorest peasantry will be conscious of this, will make Russia many

times stronger in the military respect, especially after a complete break with

the capitalists who rob the people, not to mention that then the war on our

side will be, not in words, but in fact, a war in alliance with the oppressed

peoples of the whole world."

The question

of Revolutionary wars was so integral to and bound up with October revolution

itself, that when Kamenev and Zinoviev argued against the prospects of October

Revolution, their prime concern was the fear of a revolutionary war. In their

open letter to Party, they wrote: "The

masses of soldiers support us because we advance not a slogan of war, but a

slogan of peace…If we seize power alone now and if we find ourselves compelled

by the entire world situation to engage in a revolutionary war, the soldier

masses will recoil from us."

It is not

surprising that both Zinoviev and Kamenev, supported the idea

of immediate signing of the peace treaty with Germany.

Reasserting

his pacifism, Stalin claimed: ‘There is no revolutionary movement in the West,

nothing existing, only a potential, and we cannot count on a potential.’

Lenin

forthwith repudiated Stalin’s position. ‘Can’t take the revolution in the West

into account?’, Lenin exclaimed on Stalin’s position, “It was true the

revolution in the West had not yet begun, but if we were to change our tactics

on the strength of that ... then we would be betraying international

socialism.”

Echoing

Stalin, and failing to see the grounds for expecting revolution in the West, Zinoviev added, “... of course ... peace will strengthen chauvinism in Germany and for a

time weaken the movement everywhere in the West.”

Lenin

opposed Zinoviev, saying, “it is wrong to say that concluding a peace will

weaken the movement in the West for a time. If we believe that the German

movement can immediately develop if the peace negotiations are broken off then

we must sacrifice ourselves, for the power of the German revolution will be

much greater than ours.”

Lenin did

not deny the revolutionary potential in the West: “Those who

advocate a revolutionary war, point out that this will involve us in a civil war

with German imperialism and in this way we will awaken revolution in Germany.

But Germany is only just pregnant with revolution and we have already given

birth to a completely healthy child, a socialist republic, which we may kill if

we start a war.”

It must be

clearly understood that Lenin’s insistence upon a peace treaty at Brest-Litovsk was not aimed

at pacifist defence of the Soviet State against Imperialism, but was aimed at bargaining a breathing space to prepare for

Revolutionary wars in future, against Imperialism.

Looking

back, later, upon Brest-Litovsk, Lenin clarified: "At the

Brest-Litovsk peace we had to go in the face of patriotism. We said: if you are

a socialist, you must sacrifice your patriotic feelings in the name of the

international revolution, which is coming, which has not yet come, but in which

you must believe if you are an internationalist."

Trotsky

reflected the same sentiments in his writings and speeches on Brest-Litovsk,

which were compiled and published in Lenin’s lifetime, but no dispute ever was

raised.

After death of Lenin in 1924, Stalinists started the dirty blame game against Trotsky that he was opposed to Lenin and put the security of Soviet State at stake by refusing to sign the treaty of Brest-Litovsk. The recorded facts, speak contrary to this propaganda of Stalinists.

The official protocols of the CC meetings, published by the Stalinist State itself (State Publishers, 1929) that probably escaped from watchful eye of Saveliev, the editor of State Protocols, speak for themselves. Let us have a look at them to find the truth and forgery of Stalin and Stalinists:

Sessions of January 24, 1918.

What was Stalin’s attitude to the formula of Trotsky?

“Session of February 1 (January 19), 1918.

Session of February 23, 1918.

Before taking a somersault, as he always did, to keep clinging to the majority advocating an immediate signing of the Treaty, Stalin clearly supported the stance of Trotsky, as the majority in the Party and the Soviets at that time was in favour of rejection of the Treaty and for revolutionary war against Germany and only Trotsky had a 'way out' of the impasse, i.e. a mid-way.

After death of Lenin in 1924, Stalinists started the dirty blame game against Trotsky that he was opposed to Lenin and put the security of Soviet State at stake by refusing to sign the treaty of Brest-Litovsk. The recorded facts, speak contrary to this propaganda of Stalinists.

The official protocols of the CC meetings, published by the Stalinist State itself (State Publishers, 1929) that probably escaped from watchful eye of Saveliev, the editor of State Protocols, speak for themselves. Let us have a look at them to find the truth and forgery of Stalin and Stalinists:

Sessions of January 24, 1918.

Comrade Trotsky moves the following formula to a vote: We

terminate the war, but we do not conclude peace. The vote is taken. Carried: 9-

for; 7- against.” (Idem., p.207.)

What was Stalin’s attitude to the formula of Trotsky?

Here is what Stalin had to say on record one week after

the session at which this formula had been adopted by a vote of 9 to 7.

“Session of February 1 (January 19), 1918.

Comrade Stalin: “... the way out of the difficult

situation was provided us by the middle point of view, the position of

Trotsky.” (Idem., p.214.)

Session of February 23, 1918.

Comrade Stalin: ‘We

need not sign but we must begin peace negotiations’.

Before taking a somersault, as he always did, to keep clinging to the majority advocating an immediate signing of the Treaty, Stalin clearly supported the stance of Trotsky, as the majority in the Party and the Soviets at that time was in favour of rejection of the Treaty and for revolutionary war against Germany and only Trotsky had a 'way out' of the impasse, i.e. a mid-way.

Even while

supporting Lenin on Brest-Litovsk, and speaking for the Party, Kamenev, said

about the propaganda conducted at Brest-Litovsk: "our words will reach the

German people over the heads of the German generals, that our words will strike

from the hands of the German generals the weapon with which they fool the

people".

Differences in

opinion as to tactical path arose among Bolshevik leadership, only after negotiations

at Brest-Litovsk neared a break on January 21, 1918. In this Lenin was in

minority and Bukharin in majority.

Differences

were direct offshoot of delay in German revolution and were of episodic

significance as to how to survive till German revolution, in the teeth of the

disastrous terms of proposed Treaty on the one hand and the German military

assault on the other.

Lenin

demanded immediate signing of the treaty, Bukharin an outright rejection and

Revolutionary War against Germany, Trotsky prolonging the negotiations and

signing only in case of an actual assault.

When the

three positions were put to the vote, in CC of the Party, Lenin received 15

votes, Trotsky 16 and Bukharin’s call for ‘revolutionary war’ 32.

Trotsky advanced

his proposal to the vote: ‘go for armistice, do not conclude peace, and

demobilise the old army’. The vote on this proposal in CC was: nine for, seven against.

The central committee, thus, formally authorised Trotsky to pursue this policy

at Brest-Litovsk.

Against

Zinoviev’s solitary vote, the central committee decided to ‘do everything to

drag out the signing of a peace’, that was precisely Trotsky’s position.

The

overwhelming majority of workers, however, rallied behind Bukharin and opposed

the signing of the treaty.

As the Party

turned to Soviets for advice on Brest-Litovsk, among more than two hundred that

answered, only two big soviets, in Petrograd and Sevastopol, supported peace, the

latter with conditions. All the other major soviets in prime industrial

centres-Kronstadt, Moscow, Ekaterinoslav, Ekaterinburg, Kharkov,

Ivanovo-Vozuesensk, etc, voted with huge majority to reject the proposed

Treaty.

And who were

the Leaders that supported Lenin on the question of signing of the Treaty

immediately? Zinoviev, Kamenev, Stalin!

All those who yesterday had supported Capitalist Government under Lvov

and Kerensky and opposed Lenin’s April Thesis and the idea to advance to

October, with only Stalin falling behind Lenin, later.

Those who

supported Lenin in October revolution were all against signing the Treaty and

those who had opposed the October revolution, were supporting the immediate

signing of the Peace Treaty of Brest Litovsk.

On 7 (20)

January 1918, Lenin wrote in his ‘Theses on the Question of the Immediate

Conclusion of a Separate and Annexationist Peace’: “That the

socialist revolution in Europe must come, and will come, is beyond doubt. All

our hopes for the final victory of socialism are founded on this certainty and

on this scientific prognosis. Our propaganda activities in general, and the

organisation of fraternisation in particular, must be intensified and extended.

It would be a mistake, however, to base the tactics of the Russian socialist

government on attempts to determine whether or not the European, and especially

the German, socialist revolution will take place in the next six months (or

some such brief period). Inasmuch as it is quite impossible to determine this,

all such attempts, objectively speaking, would be nothing but a blind gamble.”

Lenin was

absolutely right in stating, “There can be no doubt that our army is absolutely

in no condition at the present moment to beat back a German offensive

successfully. The socialist government

of Russia is faced with the question – a question whose solution brooks no

delay – of whether to accept this peace with annexations now, or to immediately

wage a revolutionary war– In fact, no middle course is possible.”

“One should

not derive the necessary tactics directly from a general principle”, he wrote. “Some

people would argue that such a peace would mean a complete break with the

fundamental principles of proletarian internationalism. This argument, however,

is obviously incorrect. Workers who lose a strike and sign terms for the

resumption of work which are unfavourable to them, and favourable to the

capitalist, do not betray socialism.”

"Would a

peace policy harm the German revolution?" asks Lenin, and answers: “The German

revolution will by no means be made more difficult of accomplishment as far as

its objective premises are concerned, if we conclude a separate peace ...A

socialist Soviet Republic in Russia will stand as a living example to the

peoples of all countries and the propaganda and the revolutionising effect of

this example will be immense.”

On 28

January (10 February) Trotsky broke off negotiations with the Quadruple

Alliance, declaring that while Russia refused to sign the annexationist peace,

it also simultaneously declared its unilateral withdrawal from the war.

In a bitter

indictment of imperialism, Trotsky asserted, “We are removing our armies and

our people from the war. Our peasant soldiers must return to the land to

cultivate in peace the field which the revolution has taken from the landlord

and given to the peasants. Our workmen must return to the workshops and

produce, not for destruction, but for creation. They must, together with the

peasants, create a socialist state.

We are going

out of the war. We inform all peoples and their governments of this fact. We

are giving the order for a general demobilisation of all our armies opposed at

present to the troops of Germany, Austria-Hungary, Turkey and Bulgaria. We are

waiting in the strong belief that other peoples will soon follow our example.

At the same

time we declare that the conditions as submitted to us by the governments of Germany

and Austria-Hungary are opposed in principle to the interests of all peoples.

These conditions are refused by the working masses of all countries, amongst

them by those of Germany and Austria-Hungary ... We cannot place the signature

of the Russian Revolution under these conditions which bring with them

oppression, misery and hate to millions of human beings. The governments of

Germany and Austria-Hungary are determined to possess lands and peoples by

might. Let them do so openly. We cannot approve violence. We are going out of

the war, but we feel ourselves compelled to refuse to sign the peace treaty.”

As Trotsky still

stayed on at Brest-Litovsk the next day, he learned of the strife between

General Hoffmann, who insisted on the resumption of war against Russia, and the

civilian diplomats Kühlmann and Czernin, who favoured accepting the soviet

proposal of armistice. As General Hoffman was isolated, it seemed peace was on

cards. Trotsky returned to Petrograd confident that the policy would work.

Historian Wheeler-Bennett

described Trotsky’s achievements at Brest-Litovsk: “Single-handed, with nothing

behind him, except a country in chaos and a regime scarcely established, this

amazing individual, who a year before had been an inconspicuous journalist

exiled in New York, was combatting successfully the united diplomatic talent of

half Europe.”

Pravda excitedly

proclaimed, “The Central Powers are placed in a quandary. They cannot continue

their aggression without revealing their cannibal teeth dripping with human

blood. For the sake of the interests of socialism, and of their own interests,

the Austro-German working masses will not permit the violation of the

revolution.”

On 1 (14)

February Trotsky gave a lengthy report on the peace negotiations to the central

executive committee of the soviets, in the conclusion of which he said, “Comrades,

I do not want to say that a further advance of the Germans against us is out of

the question. Such a statement would be too risky, considering the power of the

German Imperialist Party. But I think that by the position we have taken up on

the question we have made any advance a very embarrassing affair for the German

militarists.”

On February

14, the Soviet Central Executive Committee discussed and adopted a resolution moved

by Sverdlov on behalf of the Bolshevik faction, on the action Trotsky had taken

in refusing to sign the Treaty and break off the negotiations. The resolution

said, "Having heard and fully considered the report of the peace

delegation, the Central Executive Committee fully approves of the action of its

representatives at Brest-Litovsk." Approving the action of Trotsky,

Zinoviev said at the Party Congress held in March 1918, "Trotsky is right

when he says that he acted in accordance with the decision of the majority of

the Central Committee." None opposed.

Britain and

France and their agents inside Russia, like Socialist Revolutionaries had been

conducting vicious propaganda that Bolsheviks were German agents, they had been

financed by German government to take Russia out of the War and are bent upon

signing a treaty with Germany, at Russian expense.

Trotsky’s

argument was that a real German offensive would expose the masses to the truth

as to how the Bolsheviks were compelled by Germany to give up to an

annexationist Treaty. This would lay bare the real intentions of the German

imperialism and could spark protests and unrest, not only inside Germany and

Austria-Hungary, but also Entente, the alliance led by Britain and France.

Trotsky

never advocated an instant revolutionary war against Germany, but he was

against signing the peace treaty, outright. He wrote: “A

revolutionary war was impossible. About this there was not the slightest shade

of disagreement between Vladimir Ilyich and myself…

I maintained

that before we proceeded to sign the peace it was absolutely imperative that we

should prove to the workers of Europe, in a most striking manner, how great,

how deadly, was our hatred for the rulers of Germany ...

To arouse

the masses of Germany, of Austro-Hungary, as well as of the Entente – this was

what we hoped to achieve by entering into peace negotiations. Having this aim

in mind, we reasoned that the negotiations should drag on as long as possible,

in this way giving the European workers enough time to acquire a proper

understanding of the actuality of the revolution, and more especially, of the

revolution’s policy of peace.”

Trotsky insisted

to continue the armistice without signing a peace agreement.

Events in

Germany in the middle of January, 1918, started endorsing Trotsky. As Wheeler-Bennett, historian of the

Brest-Litovsk negotiations, wrote, “... a wave of strikes and outbreaks struck

through Germany and Austria. Soviets were formed in Berlin and

Vienna. Hamburg, Bremen, Leipzig, Essen and Munich took up the cry. ‘All power

to the soviets’ was heard in the streets of Greater Berlin, where half a

million workers downed tools. In the forefront of the demands were the speedy

conclusion of peace without annexations or indemnities, on the basis of the

self-determination of peoples in accordance with the principles formulated by

the Russian people’s commissars at Brest-Litovsk, and the participation of

workers’ delegates from all countries in the peace negotiations.”

On 18 (31)

January 1918 Pravda appeared with the headline: ‘It has happened! The

head of German imperialism is on the chopping block! The iron fist of the

proletarian revolution is raised!’

The first

formal discussion at the central committee of Lenin’s Theses on

Peace took place on 11 (24) January at a time when the wave of strikes in

Germany and Austria was in full flood. At this meeting a number of others who

were not central committee members were also present.

Wide

sections of the party, including the great majority of the Petersburg committee

and of the Moscow regional bureau, were in favour of a revolutionary war. The

views of many of the rank and file could be summed up in the phrase used by

Osinsky, a member of the Moscow regional bureau, “….’stand for Lenin’s old position’ Bukharin

argued for ‘revolutionary war’ against the Hohenzollerns and Hapsburgs; ‘to

accept the Kaiser’s diktat would be to stab the German and Austrian proletariat

in the back’. Dzerzhinsky reproached Lenin with timidity, with surrendering the

whole programme of the revolution: ‘Lenin is doing in a disguised form what

Zinoviev and Kamenev did in October.’ In Uritsky’s view Lenin approached the

problem ‘from Russia’s angle and not from an international point of view’.

Lomov argued that ‘by concluding peace we capitulate to German imperialism’. On

behalf of the Petrograd organization, Kosior harshly condemned Lenin’s

position.”

Defending

Lenin, but asserting his own position, Trotsky argued: “... the question of a

revolutionary war is an unreal one. The old army has to be disbanded, but

disbanding the army does not mean signing a peace ... By refusing to sign a

peace and demobilising the army, we force the facts into the open, because when

we demobilize, the Germans will attack. This will be a clear demonstration to

the German Social-Democrats that this is no game with previously determined

roles.”

Germany

issued ultimatum after break of negotiations. Lenin, still in minority,

advocated for acceptance, but Trotsky resisted.

Unfortunately,

by 3rd February the whole German-Austrian uprising ebbed into a lull, for no

apparent reason.

Lenin then

asked: "If the German offensive begins, and no revolutionary upheaval

takes place in Germany, are we still not to sign peace?"

On this

Trotsky voted in favour of Lenin, while Bukharin abstained.

Even as German

offensive started, and Lenin pressed for immediate signing of the Treaty,

Trotsky resisted. CC meeting of 18 February, noted, “Comrade Trotsky, against

sending a telegram offering peace, emphasize that the masses are only just

beginning now to digest what is happening; to sign peace now will only produce

confusion in our ranks; the same applies to the Germans, who believe that we

are only waiting for an ultimatum ... we have to wait to see what impression

all this makes on the German people. The end to the war was greeted with joy in

Germany and it is not out of the question that the German offensive will

produce a serious outburst in Germany. We have to wait to see the effect and

then – we can still offer peace if it doesn’t happen.”

As the real

German offensive began, Lenin, still in minority, threatened to resign from his

leading positions in the Party and the State. Lenin’s proposal for signing of Treaty

still lost by one vote in CC, 6 for, 7 against.

Disagreeing with Lenin, Trotsky said, “I do not think we are threatened by

destruction ... There is a lot of subjectivity in Lenin’s position. I am not

convinced that this position is right but I do not want to do anything to

interfere with party unity ...”

“The arguments of V.I. are far from convincing; if we had all been of the

same mind, we could have tackled the task of organising defence and we could

have managed it. Our role would not have been a bad one even if we had been

forced to surrender Peter [Petrograd] and Moscow. We would have held the whole

world in tension. If we sign the German ultimatum today, we may have a new

ultimatum tomorrow. Everything formulated in such a way as to leave an

opportunity for further ultimatums. We may sign a peace; and lose support among

the advanced elements of the proletariat, in any case demoralise them.”

When again in the night of Feb 21 vote was taken, Trotsky abstained

from voting, to save a split in the Party, giving majority to Lenin, in favour

of signing the Treaty. The votes were 7 for Lenin, 4 against, 4 abstentions. It was though clear that Trotsky was in majority in the CC and in case of resignation of Lenin, he would have succeeded him in Party and the Soviet State, but he humbly withdrew.

On February 21, 1918, German

provocateurs instigated a workers’ uprising in Finland, which was then crushed

brutally. Trotsky suspected that the allies might have conspired with Germany

against Russia and that Germany may resume the offensive despite a Treaty.

The treaty,

now harsher than ever, forced Russia to give up Finland, Poland and the Baltic

states plus a third of its agricultural land and three-quarters of its

industries.

After

signing of the Treaty, Trotsky resigned from his position as Foreign Commissar

on February 24, despite insistence of the central committee.

The noting says, “Comrade Trotsky points out that it is just when the peace

is being signed that he finds it unacceptable to stay because he is forced to

defend a position he does not agree with.”

Despite his resignation, Trotsky alongside Lenin got the highest number of

votes for his election to the Central Committee of the Party in the Party

Congress, convened immediately after Brest-Litovsk Treaty.

However, the

harshness of the treaty, which extracted from Russia its critical means of

economic survival, set a precedent that the Allies turned against Germany while

imposing reparations on it in the 1919 Treaty of Versailles.

The signing

of the treaty of Brest-Litovsk, unleashed a civil war in Russia that became a

battle between the old reactionary White and newly formed Red Army. The Whites

wanted to continue supporting Britain, France and the newly-joined U.S. The

Bolshevik Red army opposed them and eventually drove thousands of White

Russians into exile.

The Red

army's victories in civil wars, gave Russia confidence of being a strong

military power that could stand up to western powers now.

Immediately

after the Brest-Litovsk controversy, disputes arose on the question of

accepting aid from Britain and France. The motion of acceptance was moved by

Trotsky, opposed by Bukharin and the "lefts" and supported by Lenin. Supporting

Trotsky in his note, Lenin said, "I request you to add my vote in favour

of taking potatoes and ammunition from the Anglo-French imperialist

robbers."

Interesting

would be note that in 1920, when Russia already had raised a Red Army, similar disputes,

but in changed settings, arose among Bolsheviks on the issue of war with Poland

too. Trotsky, for political and military reasons, advocated a defence for

Russia, but against an aggression inside Poland. Lenin, however, advocated a ‘Revolutionary

War’ against Pilsudski regime through military intrusion inside Poland, to

incite workers in Warsaw and other cities, for a revolution. After initial

successes, the Red Army was defeated outside Warsaw. Defeated, the Bolsheviks

were forced to cede a large area of Byelorussia to Poland, which separated

Germany and Lithuania from the Soviet Republic.

Despite defeat,

the action of Lenin was a significant and salutary example and advance of the

Bolshevik policy of ‘Revolutionary War’ against capitalist countries, that

needed be followed in closer foot-steps and replicated.

Trotsky’s

presence in Brest-Litovsk was of historic significance. Immediately upon his

arrival at Brest Litovsk, he made Radek, the editor of German revolutionary

paper, ‘Die Fackel’ who accompanied him, to distribute revolutionary pamphlets

to the soldiers at greeting ceremony. Trotsky refused to attend the pre-scheduled

dinner with the Prince of Bavaria or other leaders and officials of the

Imperialist German state.

Count

Czernin, the representative of Austro-Hungarian monarchy, underlining the immense

moral influence of Trotsky, noted in his diary: ‘The wind seems to be in a very

different quarter now from what it was.’

As German

representative Von Kuhlmann and Max Hauffman read out the peace treaty,

demanding annexation of large regions of Russia to Germany, Trotsky broke

negotiations and left for Petrograd.

On 1 (14) February

General Hoffmann denounced the Bolsheviks because their government was

supported by force. Trotsky replied: “The general

was quite right when he said that our government rests on force. Up to the

present moment there has been no government dispensing with force. It will

always be so as long as society is composed of hostile classes ... What in our

conduct strikes and antagonises other governments is the fact that instead of

arresting strikers we arrest capitalists who organise lockouts; instead of

shooting the peasants who demand land, we arrest and we shoot the landlords and

the officers who try to fire upon the peasants ..."

Hoffmann’s face grew purple. Austrian

representative to negotiations, Czernin, comments in his diary: ‘Hoffmann made

his unfortunate speech. He had been working on it for several days, and was

very proud of.’

As we look

in retrospect at Brest Litovsk, it is all the more clear, that the tactical

positions of Lenin and Trotsky were too close to each other, and depended on a

whole, unforeseeable series of episodic events for their ratification by the

history. Had the workers’ uprising of January in Germany and Austria developed

into a revolution, or the WWI turned against the central powers a bit earlier,

Trotsky’s formula would have been

endorsed, otherwise Lenin’s was to succeed.

Trotsky dragged

the negotiations as long as he could in order to give the European masses the chance

of understanding the real meaning of the Soviet state and its policies. The

January 1918 strikes in Germany and Austria showed that this effort could have

been of crucial significance. The final result could have been otherwise at any

turn.

In an act of

utmost humility of a revolutionary, Trotsky declared to a session of the

central executive committee of the soviet, on 3 October 1918: “I regard it

my duty to declare, in this authoritative assembly, that at the time when many

of us, myself included, doubted whether it was necessary or permissible for us

to sign the peace of Brest-Litovsk, whether perhaps doing this would not have a

hampering effect on the development of the world proletarian movement, it was

Comrade Lenin alone, in opposition to many of us, who with persistence and

incomparable perspicacity maintained that we must undergo this experience in

order to be able to carry on, to hold out, until the coming of the world

proletarian revolution. And now, against the background of recent events, we

who opposed him are obliged to recognise that it was not we who were right.”

However, evidence,

emerging later, pointed to a definite yearning of central powers against war,

fearing revolutions in their own countries. Austrian representative, Czernin’s

diary, crucial piece of such evidence, demonstrates beyond any pale of doubt

that the authorities in Vienna were fearing starvation and revolt in their

countries, in case of a failure of peace negotiations. As Austro-Hungarian

empire already rested on the verge of a real collapse, Czernin had threatened

his German colleagues with separate negotiations with Russia.

Wheeler-Bennett

describes Czernin’s position in these words: ‘Peace at any price became his

motto ... Austria reached the end of her military power, her political

structure was doomed.’ On 17 November 1917 Czernin wrote to one of his

friends, “To settle with Russia as speedily as possible, then break through the

determination of the Entente to exterminate us, and then to make peace – even

at a loss – that is my plan and the hope for which I live.”

An entry in

Czernin’s diary of 23 December 1917 states, “Kühlmann is personally an advocate

of peace, but fears the influence of the military party, who do not wish to

make peace until definitely victorious.”

Another entry

for 27 December 1917 reads, “Matters still getting worse ...I told Kühlmann and

Hoffmann I would go as far as possible with them; but should their endeavours

fail then I would enter into separate negotiations with the Russians ...

Austria-Hungary ... desires nothing but final peace. Kühlmann understands my

position, and says he himself would rather go than let it fail. Asked me to

give him my point of view in writing, as it ‘would strengthen his position’.

Have done so. He has telegraphed it to the Kaiser.”

Entry of 7

January 1918, says, “A wire has just come in reporting demonstrations in

Budapest against Germany. The windows of the German Consulate were broken, a

clear indication of the state of feeling which would arise if the peace negotiations

were to be lost ...”

On 15

January 1918, Czernin wrote, “I had a letter today from one of our mayors at

home, calling my attention to the fact that disaster due to lack of foodstuffs

is now imminent. I immediately telegraphed the Emperor as follows: ‘I have just

received a letter from Statthalter N.N. which justified all the fears I have

constantly repeated to Your Majesty, and shows that in the question of food

supply we are on the very verge of a catastrophe. The situation arising

out of the carelessness and incapacity of the Ministers is terrible, and I

fear it is already too late to check the total collapse which is to be expected

in the next few weeks ... On learning the state of affairs, I went to the Prime

Minister to speak with him about it. I told him, as is the case, that in a few

weeks our war industries, our railway traffic, would be at a standstill, the

provisioning of the army would be impossible, it must break down, and that

would mean the collapse of Austria and therewith also of Hungary. To each of

these points he answered yes, that is so ... We can only hope that some ‘deus

ex machina’ may intervene to save us from the worst.”

On 17

January 1918, diary notes, “Very bad news from Vienna and environs. Serious

strike movement due to the reduction of flour rations and the tardy progress of

the Brest negotiations.”

On the same

day Czernin got a message from the Austrian emperor that stated, “I must once

more earnestly impress upon you that the whole fate of the monarchy and of the

dynasty depends on peace being concluded at Brest-Litovsk as soon as possible

... If peace be not made at Brest, there will be revolution.”

On 20

January Czernin writes in his diary, “The position now is this: without help

from outside, we shall ... have thousands perishing in a few weeks ... if we do

not make peace soon then the troubles at home will be repeated, and each

demonstration in Vienna will render peace here most costly to obtain ...”

Diary shows

that the Austrians were supported in their attempts to concede to Soviet

proposal for peace without annexations, by the Bulgarians and Turks, and, much

more important, by the German foreign minister von Kühlmann and prime minister

von Hertling.

Czernin

describes the reaction to Trotsky’s ultimatum of 10 February to withdraw from

the negotiations, “At a meeting on 10 February of the diplomatic and military

delegates of Germany and Austria-Hungary to discuss the question of what was

now to be done it was agreed unanimously, save for a single dissentient, that

the situation arising out of Trotsky’s declarations must be accepted. The one

dissentient vote – that of General Hoffmann – was to the effect that Trotsky’s

statement should be answered by declaring the end to armistice, marching on

Petersburg and supporting the Ukraine openly against Russia. In the ceremonial

final sitting, on 11 February, Herr von Uhlmann adopted the attitude expressed

by the majority of the peace delegations and set forth the same in a most

impressive speech.

The Austrian

delegation wired to Vienna that peace had been concluded, with the result that

the imperial capital was even now dressing itself en fête.

With the

sincere hope of peace in his heart, Uhlmann brought the conference proceedings

to a format conclusion on 11 February and departed for Berlin.

However at

this point the tide started to turn against von Uhlmann. On his

arrival in Berlin he was summoned, by the chancellor and the

vice-chancellor ... to the little watering place of Homburg, where the Kaiser

was taking a February cure. There, throughout the 13th, raged a battle royal on

the issues of peace and war, with the Emperor flitting in and out like an

unhappy ghost.”

The

civilians remained opposed to the high command. They feared the effect on the

internal conditions of Germany if hostilities were resumed ... Uhlmann, in

addition to his general principles, warned them that a new war in the east

would strain the alliance with Austria-Hungary almost to the breaking point

...

The memoirs

of Ludendorff and Uhlmann make it clear that for days there was a balance

between the war party headed by the German military staff (Hindenburg,

Ludendorff and Hoffmann), and the peace party, headed by von Kühlmann and von

Hertling. The latter argued repeatedly that the situation on the home front did

not permit a military offensive against the Russians. But the German supreme

command remained adamant. In the end, with the Kaiser’s backing, a few days

later General Hoffman declared the armistice at an end and ordered German

troops to march on Petrograd.

In a speech

to the Petrograd Soviet on 4 (17) November, 1917, before start of negotiations at Brest Litovsk, Trotsky explained how he

visualized the role of Soviet representatives in the peace negotiations: “Sitting at

one table with the representatives of our adversaries we shall ask them

explicit questions which do not allow of any evasion, and the entire course of

negotiations, every word that they or we utter, will be taken down and reported

by radio telegraph to all peoples who will be the judges of our discussions.

Under the influence of the masses, the German and Austrian governments have

already agreed to put themselves in the dock. You may be sure, comrades, that

the prosecutor, in the person of the Russian revolutionary delegation, will be

in its place and will in due time make a thundering speech for the prosecution

about the diplomacy of all imperialists.”

A couple of

weeks later, on 23 November (6 December), Trotsky issued an appeal To the

Toiling People of Europe, Oppressed and Bled White: “We conceal

from nobody that we do not consider the present capitalist governments capable

of a democratic peace. Only the revolutionary struggle of the working masses

against present governments can bring Europe towards such a peace. Its full

realisation will be guaranteed only by a victorious proletarian revolution in

all capitalist countries... in

entering negotiations with present governments ... the Council of People’s

Commissars does not deviate from the path of social revolution.

... In the

peace negotiations the Soviet power sets itself a dual task: first, to secure

the quickest possible cessation of the shameful and cruel slaughter which

destroys Europe, and secondly, to aid, with all means available to us, the

working class of all countries to overthrow the rule of capital and to seize

state power in the interests of democratic peace and socialist transformation

of Europe and of all mankind.”

As Foreign Commissar

in Soviet Union, Trotsky set a precedent as to how the revolutionary agitation

must be conducted.

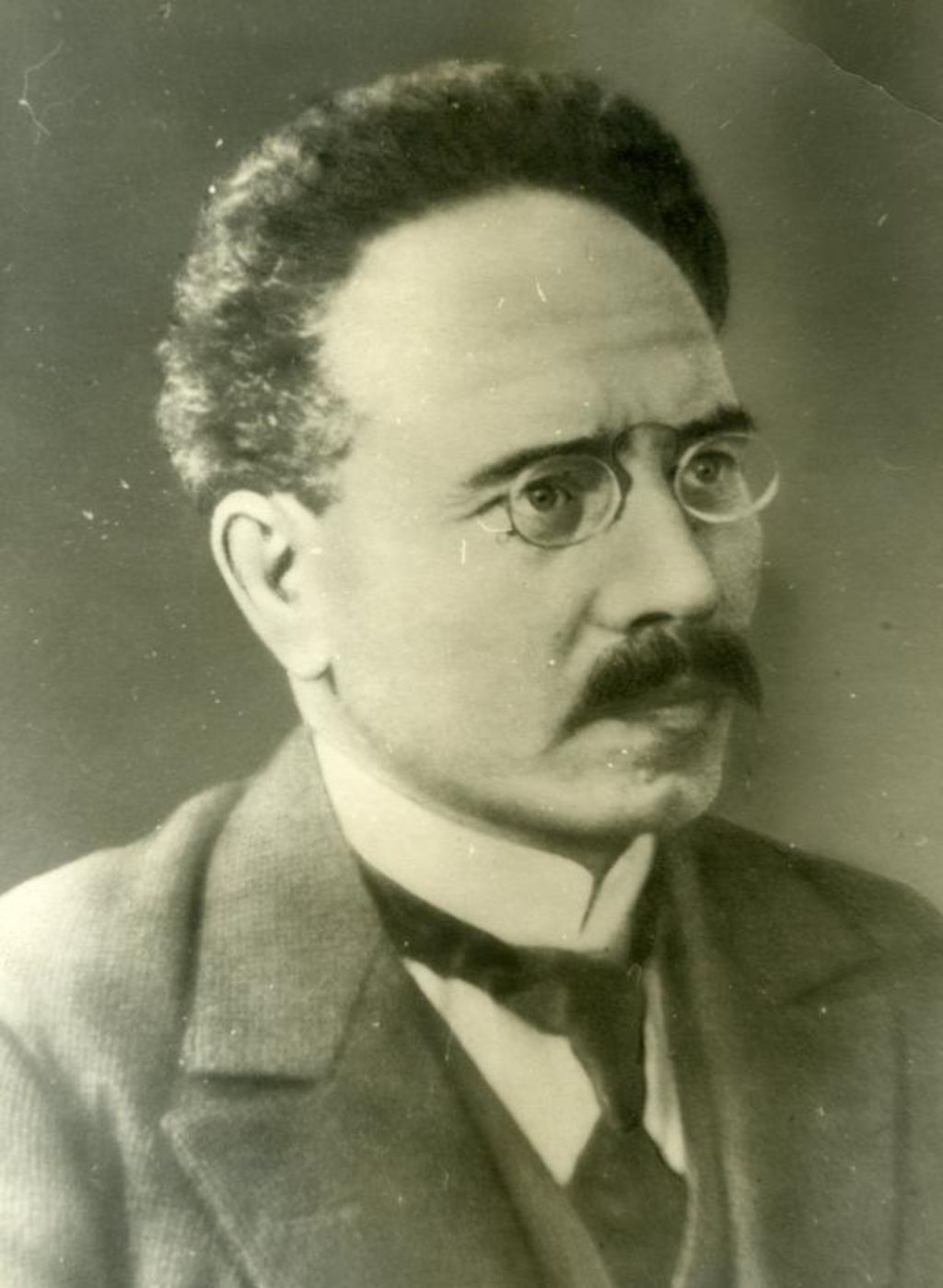

The German

revolutionary socialist Karl Liebknecht, from his prison cell, wrote that the

policy of prolonged negotiations carried by Trotsky in Brest was of great political

advantage to the revolution in Germany, “The result of Brest-Litovsk is not

nil, even if it comes to a peace of forced capitulation. Thanks to the Russian

delegates, Brest-Litovsk has become a revolutionary tribunal whose decrees are

heard far and wide. It has brought about the exposure of the Central Powers; it

has exposed German avidity, its cunning lies and hypocrisy. It has passed an

annihilating verdict upon the peace policy of the German Social Democratic majority – a policy which is not so much a pious hypocrisy as it is cynicism.

It has proved powerful enough to bring forth numerous mass movements in various

countries.”

“An early

signing of peace by the Soviets would have damaged the German

revolution”, claimed Liebknecht, “In no sense can it be said that the present

solution of the problem is not as favourable for the future development as a

surrender at Brest-Litovsk would have been at the beginning of February. Quite

the contrary. A surrender like that would have thrown the worst light on all

preceding resistance and would have made the subsequent submission to force

appear as ‘vis haud ingrata’. The cynicism that cries to heaven and the brutal

character of the ultimate German action have driven all suspicions into the background.”

Lenin was

not totally against Trotsky’s tactical line. Krupskaya discloses Lenin’s

hesitation, how on an evening stroll with her, Lenin kept assuring himself that

position of Trotsky was not correct. But way back, Krupskaya tells, “Ilyich

suddenly stops and his tired face lights up and he lets forth: ‘You never

know’!” – clearly meaning a revolution may have started in Germany!

Trotsky well

knew that had he signed the peace treaty sooner, the Soviet republic might have

obtained less harsh terms. In that case, however, German imperialism would not

have been completely unmasked, nor would the myth of Bolshevik connivance with

it have been so effectively discredited. The German and Austro-Hungarian empire

hung on for nine months after the Brest-Litovsk peace, until November 1918, but

the propaganda carried on by Trotsky in the peace negotiations played a

significant role in their exposure to their own people. History has shown

beyond doubt that Brest-Litovsk negotiations had played a crucial role in the

inner collapse of the Central Powers.

As history

had shown, the hopes of Bolshevik leaders upon a revolution in the West,

especially on the one impending in Germany, were not unfounded and misplaced.

Revolution started in Germany, later in the year, with sailors of the High Seas

Fleet, stationed at Kiel, rising in mutiny, on October 29,1918, heralding the

revolution. With this jolt, Germany lost in WWI, Turkey was forced to sign separate

armistice with Allied forces, followed by Austria-Hungary on November 3, Kaiser

abdicated on November 9, and WWI ended on November 11. However, the betrayal of

social-democracy prevented the working class from taking to power and German

bourgeois republic was born.

Despite

their tactical differences, on Brest-Litovsk, both Lenin and Trotsky saw the

foreign policy of the Soviet republic as subordinate to the needs of the

international workers’ revolution. However, in later years Stalinists were to

depict Lenin’s policy as one of peaceful coexistence with the capitalist world in

favour of ‘socialism in one country’, falsely positing it against that of Trotsky’s

world socialist revolution.

Stalinists attempt, but in vain, to draw analogy between the Treaty of Brest Litovsk imposed upon the young soviet republic by Imperialism, against its will, towards the end of WWI, and the later war-pacts, singed by stalinist bureaucracy with Imperialists, fascist and democratic both, at the start of WWII, e.g. Stalin-Hitler Pact of 1939, Stalin-Churchill Pact of 1941, or the treaties of Potsdam, Yalta or Tehran. This analogy is outright false on the face of it. While the avowed purpose of revolutionary soviet regime under Lenin and Trotsky, inspired by proletarian internationalism, was to break with all blocs of Imperialists and come out of the Imperialist war at all costs, which they really achieved, the aim of the stalinist bureaucracy in signing war pacts with imperialists, was sectarian and nationalist, to enter the imperialist war, and remain an active participant in it, bound up with one or the other camp of imperialists, throughout. None of these pacts was aimed at withdrawal from the imperialist war. On the contrary, they were outright war pacts for annexations and sharing of war booty. These pacts had tagged soviet union to imperialist wars.

One cannot fail to see that the reactionary war policy of stalinist bureaucracy during WWII was in fact the obverse side of that under Lenin and Trotsky during WWI. While the policy of Lenin and Trotsky succeeded in bringing the imperialist war, WWI, to a creeching halt, the policy of stalinists, epitomised by the Stalin-Hitler war pact of August 1939, opened the gates for the imperialist war, WWII.

Stalinists attempt, but in vain, to draw analogy between the Treaty of Brest Litovsk imposed upon the young soviet republic by Imperialism, against its will, towards the end of WWI, and the later war-pacts, singed by stalinist bureaucracy with Imperialists, fascist and democratic both, at the start of WWII, e.g. Stalin-Hitler Pact of 1939, Stalin-Churchill Pact of 1941, or the treaties of Potsdam, Yalta or Tehran. This analogy is outright false on the face of it. While the avowed purpose of revolutionary soviet regime under Lenin and Trotsky, inspired by proletarian internationalism, was to break with all blocs of Imperialists and come out of the Imperialist war at all costs, which they really achieved, the aim of the stalinist bureaucracy in signing war pacts with imperialists, was sectarian and nationalist, to enter the imperialist war, and remain an active participant in it, bound up with one or the other camp of imperialists, throughout. None of these pacts was aimed at withdrawal from the imperialist war. On the contrary, they were outright war pacts for annexations and sharing of war booty. These pacts had tagged soviet union to imperialist wars.

One cannot fail to see that the reactionary war policy of stalinist bureaucracy during WWII was in fact the obverse side of that under Lenin and Trotsky during WWI. While the policy of Lenin and Trotsky succeeded in bringing the imperialist war, WWI, to a creeching halt, the policy of stalinists, epitomised by the Stalin-Hitler war pact of August 1939, opened the gates for the imperialist war, WWII.

No comments:

Post a Comment